I don’t usually put a warning in my blog posts, but I feel I should for this one. Content warning: Discussion of mental illness.

Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II (SSH2) is a sequel to Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice (HSS).

When I wrote my post on my top-rated games, I’d forgotten about HSS. I’ve just edited that post to mention the game.

Here’ what I wrote about the earlier game:

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice is an unusual video game in that the lead character is psychotic. I’m not using the term in its popular (and incorrect) sense of meaning “psychopath.” Senua is clinically psychotic: she hears voices in her head, experiences illusions, is compelled to match patterns visually, and occupies what is (probably) a world of her own. I say “probably” because the game does not bother to distinguish between the “real” and the “fantasy” of Senua’s world.

Short version: Although SSH2 has some technical improvements over HSS, and the acting is still amazing, I felt the overall experience of the later game was not as good as the first.

First, the positives

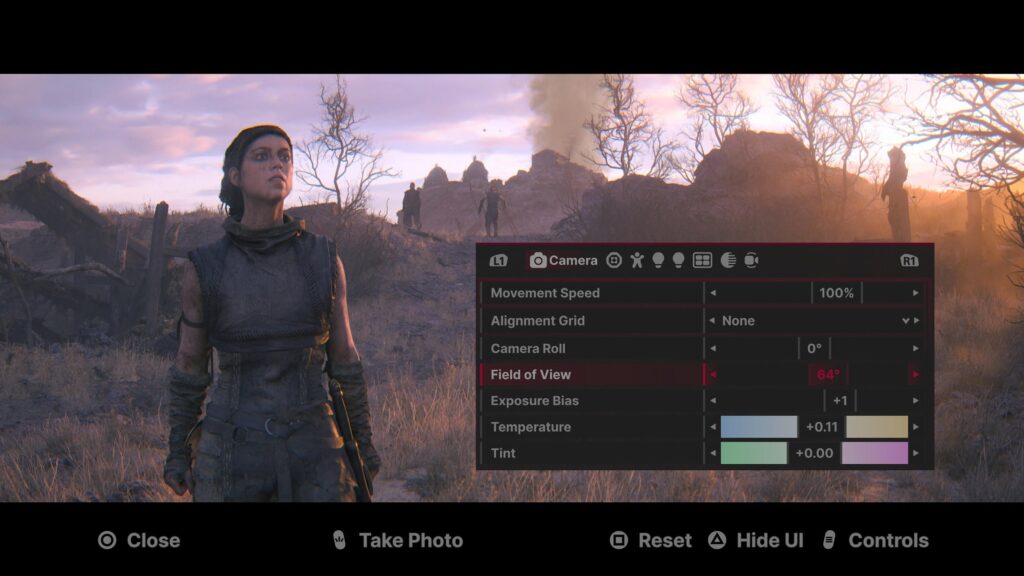

Technically, the graphics have improved considerably. In HSS, the character of Senua was the only human figure that was rendered; any other characters (figures in Senua’s memories) were video overlays. In SSH2, all the human figures are rendered along with Senua. This is gives a visually consistent look.

Similarly, the environmental design is much improved. At this point when I describe a video game I keep using words like “vivid” and “stunning”. Those words apply here as well. The color palette tends towards the dark, but this is a dark story; here the visuals match the story being told.

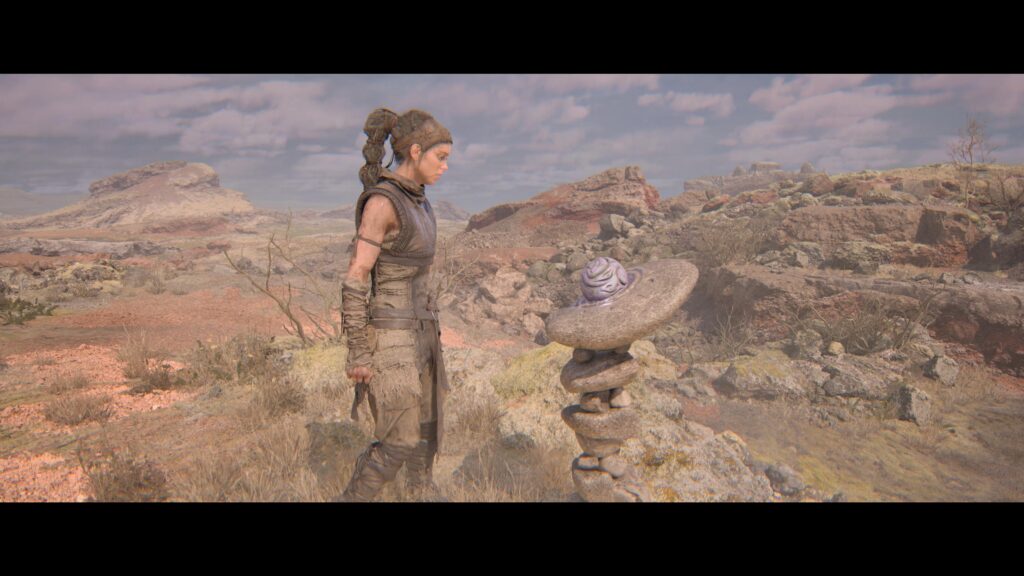

As in the first game, there are puzzles. Some of them were like those in HSS: a compulsive need to match patterns in the environment. Others were procedural: how to move stone A into slot B.

The game did not make it clear whether those puzzles were also part of Senua’s perception of the world. That suited me fine. The puzzles weren’t too difficult, and I got through them all without external hints. I enjoyed them.

There were also obstacle-course challenges: Go from point A to point B while the environment tries to kill you. I don’t enjoy this sort of thing, but I got through them all in just a few tries. They were not as difficult as those in some of the Uncharted games.

Now we get to the finest part of the game: the performance of Melina Juergens, who portrays Senua. She was brilliant in the earlier game, and she’s brilliant here. When awards are given out for video-game performance, I’ll be stunned if she doesn’t walk away with all of them.

For what it’s worth, both games are short. It took me about 12 hours to go through each one.

But…

If I were praising SSH2 on its own, I would say it was a good video game. However, I can’t help but compare it to its predecessor. In my eyes, the gameplay and story feel like a let-down from the prior game.

In discussing the difference between the two games, I have to acknowledge that I played HSS eight years ago, and did not replay it for this review. Memory is a tyrant to us all. Please feel free to be skeptical of any comparisons I make. Even better, play the first game and judge for yourself!

I had two issues with SSH2:

Is psychosis a solution?

An obvious disclaimer: I’m not a mental health professional. I’m just a gamer who talks too much.

In both games, the player hears the voices that constantly murmur in Senua’s head. This is a great effect, and gives a strong impression of what it’s like to suffer through a mental illness. The voices also provide game hints; it seemed to me that the hints were less useful in the second game. The hints in the first game helped get me through the combats; in the second, they seemed generic. There’s more on combat below.

It was difficult for me to accept the transition in Senua’s mental outlook from the first game to the second. In the first game, Senua struggled with her mental illness. In the second, it’s almost as if being psychotic has become Senua’s superpower.

I’m all for people with mental illness to succeed in life and become heroes. It just seems strange that Senua is hailed by people and becomes a hero because of her psychotic perception of the world, instead of overcoming it.

In the earlier game, Senua fought monsters and fantastical creatures. It was never clear in the game whether the creatures were “real” because this was a world of mythos, whether they were other people whom Senua perceived through the fog of psychosis, or whether it was all in Senua’s imagination. That ambiguity felt meaningful in the context of the story.

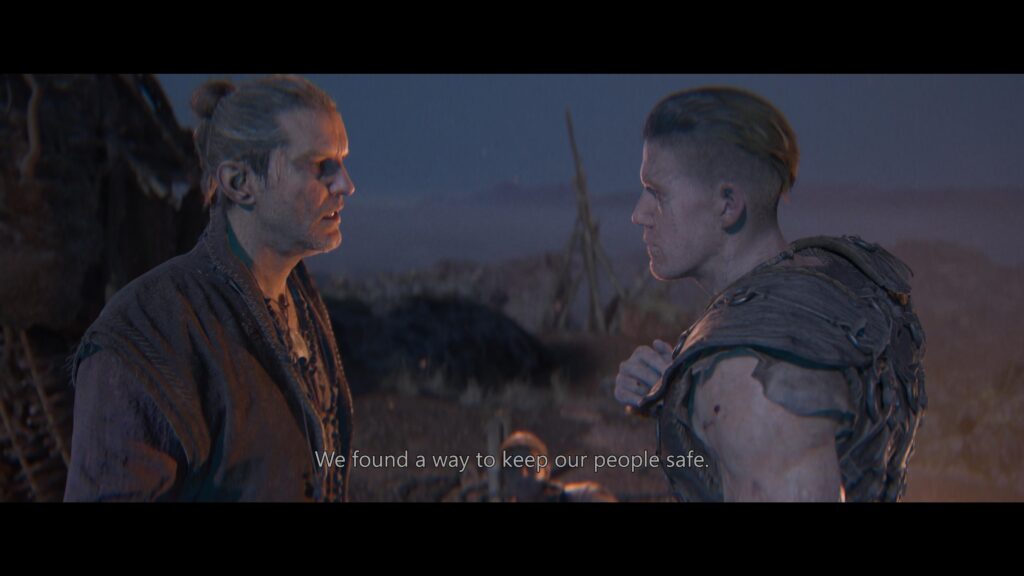

Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II is more firmly grounded in reality. Senua fights real people. She talks with others and gets confirmation that, when she finally meets monsters, that they are “real” in the context of the world she lives in. In other words, it’s not a matter of “they might be giants”; they are giants and folks tell her so.

By itself, this is a fine ideal: the story of someone with a handicap defeating monsters is one of the oldest stories in the world. In context with the earlier game, the “imaginary” monsters of Senua’s psychosis have become “real” monsters in the later game. This somehow feels like a diminishment of Senua’s growth in the first game.

Gameplay

In my review of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, I wrote:

…this is a video game, not just a travelogue through a troubled mind. The gameplay reflects Senua’s mental state: No help is given in how to play the game; if you want to know what the controller buttons do, you have to check the options screen. There are no maps or display overlays. There are no direct instructions for combat; however, the voices in Senua’s head will often give you strategy tips.

The game can be punishing, especially for a clumsy video gamer such as myself.

That remains true in SSH2.

Again, this might be my memory playing me false, but the gameplay in the second game seemed more punishing than in the first one.

My complaints echo some of those I had about Expedition 33:

Mazes

The game has many mazes. There are no minimaps or other tools to help you get through them. The voices in Senua’s head will helpfully tell you “We’re lost!” but no other clues.

In their way, these mazes were worse than the obstacle courses. I don’t remember maze navigation being an annoyance in the first game, but they’re definitely a pain in this one.

Combat

I remember combat being somewhat difficult in the first game, but I got through them all.

In SSH2, I gave up.

The game has several difficulty levels. Of course, I started on the “Easy” level. I got through the initial combats, then I got into the first “Boss battle”, with the Slaver.

The battle was interminable. The game provided no readily-identifiable clues whether I was making progress, or I continually had my butt handed to me and had to repeat combat phases. I tried to parry or dodge the opponent’s blows, but it wasn’t clear from the animations whether that was doing any good.

The game provides an even easier level: Just push the buttons. In that mode, you don’t have to select “fast” strikes versus “hard” strikes versus parries versus dodges. You just press a button, any button, and the game picks the optimal action for you.

The battle with the Slaver still just dragged on. Was I that bad of a gamer? Maybe. We all grow older and slower with time.

As I said, the whole thing reminded me of Expedition 33: I couldn’t press the button (any button!) with the right timing to accomplish anything. Or so I thought; the “no hints” philosophy of the game left me in the dark.

As in the first game, Senua’s voices supplied hints. In the first game, those hints seemed pertinent. Here they seemed generic and unhelpful: “Learn the pattern.” Yeah, right.

Finally, I went to the easiest possible combat option: The game will play the combats for you. It does everything: blows, dodges, etc. You put the controller down and essentially watch a cinematic of Senua fighting in the most optimal way.

At least that explained to me why the Slaver combat seemed interminable: It was interminable. I sat there for five minutes while my PS5 displayed the motions of the combatants.

To be fair to the game, at least I had the option of just seeing the story instead of struggling as I had with E33. The only other game I know that offers this option is NieR: Automata.

Conclusion

The first game in this cycle, Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice was amazing and memorable. This second game, Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II, was… OK. I hoped for better.

I now remember why I didn’t rank Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice higher in my list of of top-rated games: the Fire Maze. This is an obstacle course roughly in the middle of the game. I’d forgotten it, probably because it was just a frustrating disappointment in the middle of an otherwise engaging game. I had the Fire Maze thrust before me again when, as a result of writing the above review, I replayed HSS and encountered the Fire Maze again. I looked up solutions on the web, and discovered that even experienced gamers had problems with this challenge. I got through it once years ago, and maybe I’ll try again. Or not.

Pingback: Baldur’s Gate 1 and 2 – The Argothald Journal