qaStaHvIS wa’SaD wa’vatlh wa’maH wa’ jaj tlhIngan Hol vIHaDtaH. = I have studied Klingon for one thousand one hundred and eleven days.

Three Klingon-related posts in a row! However, there’s more to this particular post than the alliteration of the digit “1”: It may be my last post on Klingon.

In other words, I’ve finished the Duolingo Klingon course.

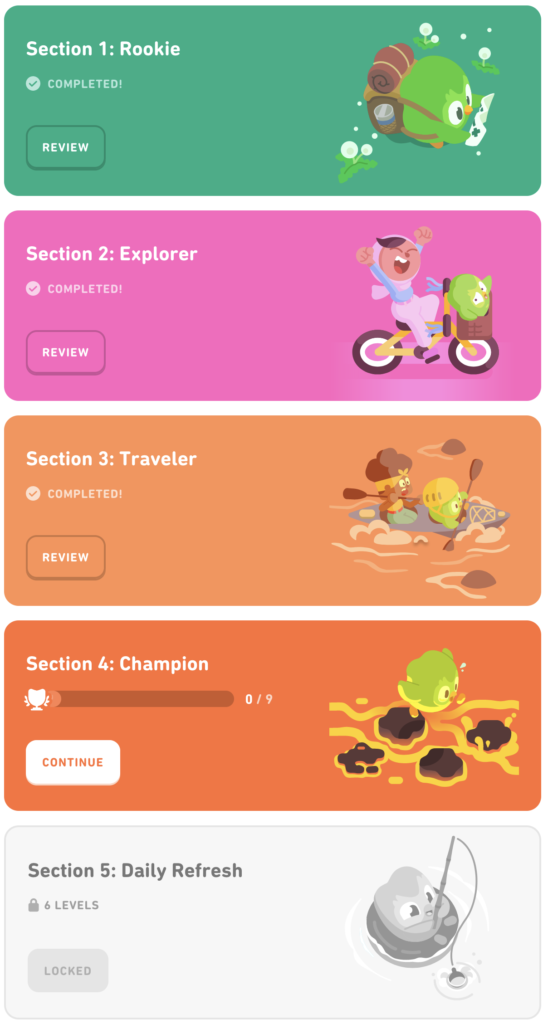

This may not be strictly true. Here’s how Duolingo describes where I’m at right now:

In my previous posts on Klingon, I described how Duolingo re-arranged all of its language course (to their detriment), then closed off further development of the Klingon course to its developers. I’m not certain, but I think that Sections 4 and 5 are entirely review; that is, they consist of exercises I’ve already seen, but in random order. I’ve asked on the Klingon Duolingo Discord channel to confirm this.

Frankly, I’m not interested in repeating material. (That’s especially true if the exercises would include more about Klingon toes.) If those Sections are just lesson reinforcement, I’m going to take a pass, and end my daily of Klingon.

This might change. If the KLI were to be allowed to update and expand the Duolingo course again, or (even better) would develop a course in some other environment, I might pick it up again. We’ll see.

Some idle thoughts

-

A friend of mine, listening to me count some cards in Klingon, commented “You must be one of the top experts in Klingon by now.”

I laughed. I’m not even close. Yes, I can speak Klingon better than 99.99% of the Earth’s population. That might be marginally helpful if the Klingon Empire were to attack.

But compared to the Klingon experts, I’m nothing. I’m thinking of Qov (Robyn Stewart) in particular; she’s one of the few people who can speak Klingon conversationally, and is a consultant on the Klingon spoken in Star Trek: Discovery and other current ST series.

From my perspective, my inability to figure out the -bogh suffix, or place a location suffixed by -Daq correctly in a sentence, makes me no more than a “baby speaker.” I know that doesn’t make much sense to most folks, but if I were to actually try to communicate in Klingon to others in forums or channels, I would sound embarrassingly naive.

-

As a constructed language, Klingon’s grammatical structure is much simpler than most real languages. That doesn’t mean it’s easy.

But the real hard part of Klingon is the vocabulary. In real-world languages, there’s usually some kind of connection between related words that makes them easier to memorize. For example, in Arabic, when you hear the consonants k t b in some combination, the word will probably have some connection to writing:

- katab = to write

- katib = writer

- maktub = letter

- kitab = book

… and so on.

In Klingon, all of the verbs and most of the nouns are three-letter consonant-vowel-consonant combinations with little or no relationship with each other. (Bear in mind that in the English-alphabet transliteration of Klingon, the combinations ch, gh, ng, tlh, and ‘ (glottal stop) are all single consonants; vowels with y or w added (such as oy or ew) are still single vowels.) In Klingon we have:

- tlhuH = to breath

- pur = to breath in

- rech = to breath out

- SoH = you

- Soch = seven

- Soj = food

- Sop = to eat

- tlhutlh = to drink

- qoq = robot

- QoQ = music

- QaQ = to be good

- ghogh = voice

- ghIgh = a necklace

- ghagh = to gargle

- ghItlh = to write

- ghatlh = to dominate

Both visually and audibly, this can turn into a mish-mash. There’s nothing aside from brute-force memorization to guide you through it, and hope that Klingons will tolerate your tera’ngan accent.

I acknowledge that this fulfills the goal of making Klingon sound like an alien language. But I found there was a point at which distinguishing between SoH and Soch became a bit much.

-

For anyone comparing my Klingon-language streak with anyone else’s: Please don’t get the impression that there are exactly 1111 Klingon-language lessons on the Duolingo course.

For one thing, when I started using Duolingo, I was unfamiliar with the concept of “streak” and lost a few days.

For another, Duolingo “gamifies” the idea of language instruction. You’re grouped with 29 other randomly-selected Duolingo users. Your accumulated weekly score is compared to that of those other users. You’re ranked on a leaderboard. The top 10 users in the group of 30 are promoted to the next rank; the bottom 5 or 10 are demoted to a lower rank.

In my early days of using Duolingo, I got caught up in the whole ranking thing. I tried to push up my rank from week-to-week to reach the topmost rank. The main way to do this is to take many lessons in a single day to boost your accumulated weekly score.

Eventually I gave this up. My goal was to learn Klingon, not to win yet another digital game.

What this means that while it took me at least 1111 days to complete the course, this both an undercount of the actual days, and it does not take into account the days in which I took multiple lessons. “1111” is an arbitrary number.

As I’ve noted before, my goal in my recent study of Klingon was to use it as Orcish in a role-playing game. In particular, I wanted to be able to express the idea of “Attack the strongest!”

The closest I got was jaghvetlh HoS law’ Hoch HoS puS ‘e’ yIHIv! My problem isn’t that the Klingon phrase is longer and less direct than the English one. It’s that after more than three years of lessons, I still don’t know whether my translation is right. The Duolingo course could only take me so far in truly understanding the language.

So what’s next?

I’m not sure. Most likely my knowledge of Klingon will fade, the same way my high-school French and college Russian courses have. I’d finally be left with a few stock phrases. (It’s interesting to note that I studied Klingon for more than three years, while I studied French and Russian for about two years each.)

If I were to start studying another language, I’d be most inclined to pick up Japanese. I’m a member of the GRAMS particle-physics detector experiment. A good number of the collaborators are in Japan. While I’m under no delusion that I’d learn enough Japanese to engage in a technical conversation with any of them, it might be nice to at least say “Hello.”

Or understand a Godzilla movie without subtitles.

One thing is for sure: Were I to try to learn yet another language, I certainly would not use Duolingo.

Pingback: 1200 Days of Klingon – The Argothald Journal